April 18, 2023

Craig Seligman on His Astonishing 'Who Does That Bitch Think She Is? Doris Fish and the Rise of Drag'

Michael Flanagan READ TIME: 11 MIN.

Doris Fish was everywhere in the 1980s. It seemed if she didn't exist someone would have had to invent her. Craig Seligman's "Who Does That Bitch Think She Is? Doris Fish and the Rise of Drag" reminds us that someone did. That someone was Philip Mills, known to all but his best friends as Doris Fish.

Seligman's biography is fast-paced, informative, funny and thoughtful. It helps that Seligman knew Doris personally through his husband Silvana Nova, who performed with Fish. The book doesn't just function as a biography of a performer. It's a history of the growth of two communities and the evolution of a consciousness.

The history of Mills' native Sydney and its drag culture includes the 1957 Artists Ball, where legendary drag artist Karen Chant, wanting to outdo Marie Antoinette's record for the most fabric in a gown, wore an outfit that "incorporated seventeen hundred yards of tulle," which was "so enormous that she had to be carted to the Trocadero in a moving van."

Doris was part of that history, too, as a member of Sylvia and the Synthetics, a genderfuck group influenced by the Cockettes that gave their first performance in October 1972. It was through the Synthetics that Doris met his lifelong friends and fellow performers Miss Abood and Carmel Strelein. Unlike the Cockettes, there was an underlying threat in the Synthetics performances. The book quotes a gay paper's warning:

"If you get too close to the stage, you're likely to be shoved back by a high-heeled shoe planted firmly on your chest."

Doris was a star in the Sydney Gay Mardi Gras, as both a participant and a planner. Many stories from the event (including one about a Falwell-like preacher whose head they patterned a float after) are hilarious.

Doris' San Francisco star was rising as well. Fish's career here began at a 1976 Tubes talent show. He and Pearl E. Gates (soon to be New Wave singer Pearl Harbour) won and became fast friends. At the talent show he met Jane Dornacker and her manager Eddie Troia, who would go on to produce the show "Blonde Sin."

In 1976, Doris also met Tippi and Miss X, and the Sluts A GoGo were born. Doris' San Francisco career took off. In the 1980s came work on the film "Vegas In Space" and plays like "Naked Brunch." I haven't even mentioned Philip's career as a sex worker or the line of Doris Fish greeting cards from West Graphics. But for those tales, you're just going to have to read the book.

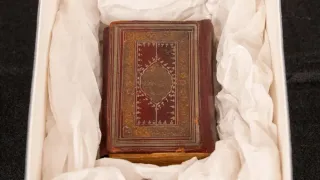

Seligman's book is a quick read as it is so compelling: I tore through the first two hundred pages in two days. The last hundred pages took a bit longer. I just didn't want to lose Doris again, although you do get to relive the community spirit that accompanied AIDS in that portion of the book. Fish's enormous talent shines in this book. "Who Does That Bitch Think She Is? Doris Fish and the Rise of Drag" has done an amazing job of preserving both the life of an incredible performer and the transformation of our world to a more accepting place via the horror of an epidemic.

Timed with a new exhibit, "Doris Fish: Ego as Artform," opening at the GLBT History Museum April 21, Seligman will discuss his book at the museum on April 28 at 6pm. I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to speak with Seligman regarding Doris' world and the book.

Michael Flanagan: Doris moved to San Francisco because it was well known in the 1970s as a gay capital (perhaps the gay capital then). I'm wondering if he also didn't move here because of hippie counterculture, and the reason I ask is because of his/her love of Grace Slick, affinity for Buddhism and diet.

Craig Seligman: Absolutely! Doris was drawn to both the hippie and the gay countercultures, and San Francisco suited him to a T. (Those were, incidentally, the same reasons I was drawn to San Francisco.) He wasn't into drugs, though.

I was very interested in the violence that Sylvia and the Synthetics incorporated into their act (and their essence). It seems as much influenced by the Warhol aesthetic as by the Cockettes. I'm wondering if there was an affinity for that world, too, and if that might be part of the reason that Miss Abood moved to New York.

Well, yes, to the extent that Warhol influenced everyone in those years (and he really did). But the kind of drag that the Warhol's superstars were doing was, on the whole, very different from the genderfuck, don't-give-a-shit drag of the Cockettes and the Synthetics, although you could argue that theirs was the next stage.

I don't see violence as part of Warhol's aesthetic, or the Cockettes', either, while for Sylvia and the Synthetics it was very much on the surface. They were rage-driven, which is what makes them, to me, so clearly forerunners of punk. Rage at the straight world – "straight" in the sense of conformist, rather than non-queer – played its part in the Cockettes' aesthetic, too, but it was submerged under their hippie-glitter surface. Anyway: the glamour of Warhol is certainly part of what drew Miss Abood to New York, and Doris would probably have wound up there, too, if he hadn't so quickly felt at home and made a name for himself in San Francisco.

How much do you think that Doris was influenced by punk in the '70s? You do mention that she shopped at Vivenne Westwood's shop Sex in London.

Doris's colleagues were influenced by punk and New Wave – or, rather, they influenced these movements themselves – but Doris was very much a child of the sixties, a flower child.

He never stopped being a hippie in his outlook. While some of his looks could be punk (there were so many!), he was much more into old-fashioned glamour. And his musical tastes ran to Grace Slick and Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez, rather than to Poly Styrene and the Slits. As far as stopping in at Sex, it was on the fashion map; it hardly made you punk to pay the shop a visit. Doris bought fishnets there, not ripped T-shirts.

There is a D.I.Y. ethos/aesthetic that runs through much of gay culture, and counter-culture generally, in both the '60s and '70s. It certainly was part of what was charming about both the Tubes and Jane Dornacker and informed both the Cockettes and John Waters world. It seems as if Doris, the Synthetics, Sluts A Go Go, and West Graphics were all informed by that aesthetic. How much do you think that the do-it-yourself impulse informed what Doris created, and do you think that she would give a go at anything that was asked of him in art and performance?

What you call a DIY impulse I see simply as an artist's inventive approach, using the available materials. Doris was doing drag before drag had been professionalized (as it is today), and he was doing it – as he was doing everything – on a shoestring. But if he'd had more money, he would have been wearing Dior and St. Laurent.

The shows, of course, were very DIY, but that, again, was because nobody had any money. You had to do it yourself because you couldn't hire anybody to do it for you. I don't see the West Graphics cards as fitting into that aesthetic at all, though. They were professionally done, with high-quality photography and color and printing.

Since the subtitle regards the rise of drag, I have to ask if Doris was aware of the Imperial Court in San Francisco, if he knew anyone involved in it and if he ever considered (either seriously or humorously) in running a campaign for Empress?

Anybody who read the Bay Area Reporter – which was everyone in the queer community – knew about the Imperial Court, but neither Doris nor any of the queens I knew had much interest in it. That was another world. My impression is that the people involved with it were more middle-class, in terms of both income and outlook.

Doris, in fact, wrote dismissively about the court in a January 5, 1990 column for the SF Sentinel titled "She Who Would Be Empress":

"Why anyone would want to run for Empress escapes me ... In pre-Stonewall and pre-Cockette days the Empress was it. It was not only politically correct (by mid-sixties standards, the Imperial Court was pretty radical stuff, after all the Emperor and Empress were gay elected officials), it was the height of camp and a lot of fun. It's still pretty camp, though now it's really serious and politically questionable."

He was dismayed by the conservatism of the Court's Board of Trustees: "If they weren't gay, would these people still be pro-gay?"

How long did it take you to research the book?

I started back in 2005, but that's a little misleading, because I had to earn a living while I was writing it. The people I needed to interview determined where my husband, Silvana Nova, and I vacationed – which wasn't such a hardship, since those interviews took us to San Francisco, L.A., Phoenix, Paris, Sydney, and Melbourne, among other places. But it was a long process; and, of course, there was also a lot of library/archival research along the way. I did my very last interview in 2019.

I wrote an earlier article on Doris' silkscreens, which were found in SoMa. Doris' visual sense was really quite impressive, both as a visual artist and as a drag performer. Has anyone ever considered doing a show of his work and/or a book of his visual art? Has your book stimulated any interest in this?

May it happen! Some of his paintings are in the Pride (R)Evolution show at the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney's equivalent of the New York Public Library. And, of course, some are currently on view at the GLBT Historical Society Museum in San Francisco. For me, though, Doris's most brilliant medium was the human face; his own and others'.

On a similar topic, is there enough recorded performance of Doris/Philip's work for a documentary?

Is there ever! Doris was one of the first people to own a home video camera, and practically all his shows in San Francisco were recorded. There's a lot of footage (which he never tired of watching), and, in fact, a Portland filmmaker named Scott Braucht is currently working on a documentary about him called "Dear Doris." (www.deardorisfilm.com)

Do you think that the deaths that Doris/Philip encountered in the '70s among the members of the Sylvia and the Synthetics prepared him at all for what we all faced in the '80s with AIDS?

No. Many people had suffered loss before AIDS; that's part of the human condition. But AIDS was terrifying and catastrophic in a way utterly different from what anyone in our generation had confronted or could even imagine.

I think our parents' generation's experience of the second World War was in some ways comparable, but there was a big difference: You didn't have, in those horrific years, a federal government that pretended nothing bad was happening, or powerful politicians and preachers who were saying that the dying were getting just what they deserved.

Since your earlier book was on Sontag and Kael and you discuss "Notes on Camp" in the book, I'm wondering how you think notions of camp had evolved from the '60s when Sontag wrote about it to when Doris was performing. Do you think Doris had his own theories regarding camp or was he indifferent to theoretical approaches to his work?

When Sontag wrote her famous essay, camp was still an elite aesthetic shared by a coterie of in-the-know gay men. In the mid-sixties it made its way into popular culture, via vehicles like the TV series "Batman" and the Bond movies. There was nothing elite or elitist about it by the time Doris was performing. That said, Doris did think deeply about his own work, and in the book I quote, for example, his analysis of what makes "Valley of the Dolls" funnier every time you watch it.

"Doris Fish: Ego as Artform," opening at the GLBT History Museum April 21 (reception 7pm-9pm ($10/free for members) through fall 2023. Craig Seligman will discuss his book at the museum with curator Ms. Bob Davis on April 28 at 6pm ($5/free for members). 4127 18th St. www.glbthistory.org

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.