April 11, 2023

Review: What's 'Enough?' Pianist Stephen Hough's New Memoir – and More

Tim Pfaff READ TIME: 6 MIN.

A music critic writing for, let's say, this newspaper could not cover every new CD release by pianist Stephen Hough. They are so numerous it would require a weekly column for Hough alone. I know; I tried it.

Designated one of the 20 living polymaths by "The Economist," Hough has, in recent years, added to his discography and busy concert schedule a welter of new musical compositions – not all of them for piano – a book of picked-up pieces including some criticism, a daring novel, a memoir, and some paintings.

Oh, and last year he was knighted by then-Queen Elizabeth. Presto: Sir Stephen Hough. All he lacks is the time for is putting a step wrong.

If there is a reason to return to him now, it's because in recent months there have been publications of his work in three bailiwicks: his string quartet, alongside Ravel's and Duttileux's, by the superb Takacs Quartet (Hyperion) (with whom Gough had previously recorded the Brahms Piano Quintet); a memoir, "Enough" (Faber and Faber); and "Musica callada," the late solo-piano suite of Federico Mompou.

The Meditative Mompou

Even devoted musicophiles could be forgiven for being unfamiliar with Mompou (1893-1987), a Spanish composer of French extraction. Hough has paved a path for the appreciation of Mompou by recording several of his colorful, beguiling miniatures on his recital CDs and in encores.

The hour-long, four-section, 28-movement "Musica callada" ("Silent Music"), composed over the years 1959 to 1967, is meditative music whose source is the writings of the 16th-century Carmelite, St. John of the Cross. What makes the music "silent" – "vaporizing," in Hough's word – is its having been pared down to its essentials. With just a few exceptions, the movements are slow in tempo, simple in expression, and anything but piano showpieces.

New to me, they reminded me of Vladimir Horowitz's assertion that he was unperturbed by the most thorny piano concertos but put in a cold sweat by "Träumerei," an achingly simple, completely exposed movement of Robet Schumann's "Kinderszenen" that poses few technical challenges. Hough has long ago demonstrated his fearlessness in tackling difficult music. His performance of the "Silent music" is devotional in all ways.

Hough's legendarily fine touch has rarely been deployed on music as austere and almost colorless as this suite. It may never have been tested to this extent before. The economy of means by both composer and pianist is remarkable, and Hough is supremely focused and steady.

The result is that both performer and listener are drawn into a quiet, only inwardly dynamic, ecstasy. It could be argued that this music is inappropriate for the recital stage, but Hough's own spirituality makes it perfect for recording and the concentrated home listening they afford. There is more than one way to be carried away.

Hough Composing Himself

Hough's String Quartet, entitled "Les Six Rencontres," is named, teasingly, String Quartet No. 1, hinting at, if not promising, a sequel. In stark contrast to the essential quiet of the "Silent Music," the quartet is active, overtly challenging technically, complex and, yet, in its own way, plain-speaking.

Its recent performance by the Takacs Quartet (with whom Hough had previously recorded the Brahms Piano Quintet) lends a welcome sense of ease to the music's sophistication. What establishes it as important music is the extent to which both the composer and his exponents care to make it communicate to an audience beyond the academy and music professionals.

With no curtailing of his concertizing, which was tellingly less interrupted by COVID than many others, Hough is increasingly focused on composition, producing a significant body of music that has won accolades from audiences and critics alike. The vocal music folds in gay subject matter as strongly yet un-sensationally that Hough is now regularly being compared, favorably, to gay musical giant Benjamin Britten.

There are some 50 compositions, some of them full-length, on Hough's website, almost all of them for scheduled public performance. Piano music is of course central by but no means the only genre. In January, four well-known singers selected by Hough performed his song cycle, "Songs of Love and Loss," at London's prestigious Wigmore Hall, and Hough will inaugurate the Wigmore's forthcoming fall season. Hough's music can be sampled on YouTube.

Hough's "Enough"

The piano is not the only keyboard at which Hough is adroit. His computer keyboards have produced reams of exemplary writing. Even the writing about music is directed at the lay reader.

His novel "The Final Retreat" looks deeply into the dilemma of a young priest attracted to and involved with young men, not too young but not infrequently "bed sits" (rent boys), and the Catholic Church, which has dispatched him to a retreat for errant priests to cleanse him. The novel has become a kind of handbook for some retreats of that type, as it doesn't demonize either side.

Structurally, "Enough" hews to the formula established in "Rough Ideas," a collection of his journalistic writings whose small sections function not unlike Nietzsche's aphorisms. True to its subtitle, "Scenes of Childhood" (that Schumann work again), it moves chronologically from a childhood recalled and evoked as vividly and mysteriously as one of Henry James's children – right up to Hough's Carnegie Hall recital, where another pianist's memoir might begin.

The book is a leap forward in Hough's already-advanced writing, substantively and as (another) practice. It's hardly the only memoir by a famous gay musician, but in many ways it's the deepest. It looks at all the facets of Hough's life, including his sexuality, with a penetrating gaze that doesn't shy away from the specific, but approaches everything with real care.

Hough was not the first classical pianist to come out, but his coming out has been the most open and articulate, forceful in its way. Being gay informs everything in his life, if not always expressly. His musing about his childhood glimpse of his father's penis approaches the transcendental.

This book is as personal as Hough's personal and stage postures are personable, preempting narcissism with warmth, modesty, and a big helping of wit.

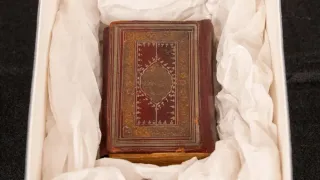

Stephen Hough's 'Enough: Scenes from Childhood,' Faber, 233 pages, $26.95

Stephen Hough's 'Federico Mompou, Musica callada,' Hyperion, $19.95

Stephen Hough's 'String Quartet, with quartets by Ravel and Dutilleux, Takacs Quartet, Hyperion,' $19.95

Help keep the Bay Area Reporter going in these tough times. To support local, independent, LGBTQ journalism, consider becoming a BAR member.