September 16, 2022

2022 Toronto Int. Film Fest Diary: Entry 3 - All That 'Joker' Drama

C.J. Prince READ TIME: 5 MIN.

As TIFF enters its closing weekend, things are winding down. The weather is colder, the press screenings are emptier, and most people are playing catch up with titles they missed in the first several days. My schedule is lighter too, meaning less movies to see, and more time to focus on the drama that's been happening off screen. Things started on the second day when Ulrich Seidl's film "Sparta" was pulled from the festival over an article that claimed the child actors in the film were exploited and mistreated during the shoot (Seidl issued a statement denying all the allegations). This controversy can open the door to bigger discussions about the purpose of a film festival, who it's in service to, and whether there could ever be a context in which the film could still be shown, but that discussion won't happen at TIFF. They're too obsessed with optics to risk blowback, and so "Sparta" will premiere elsewhere.

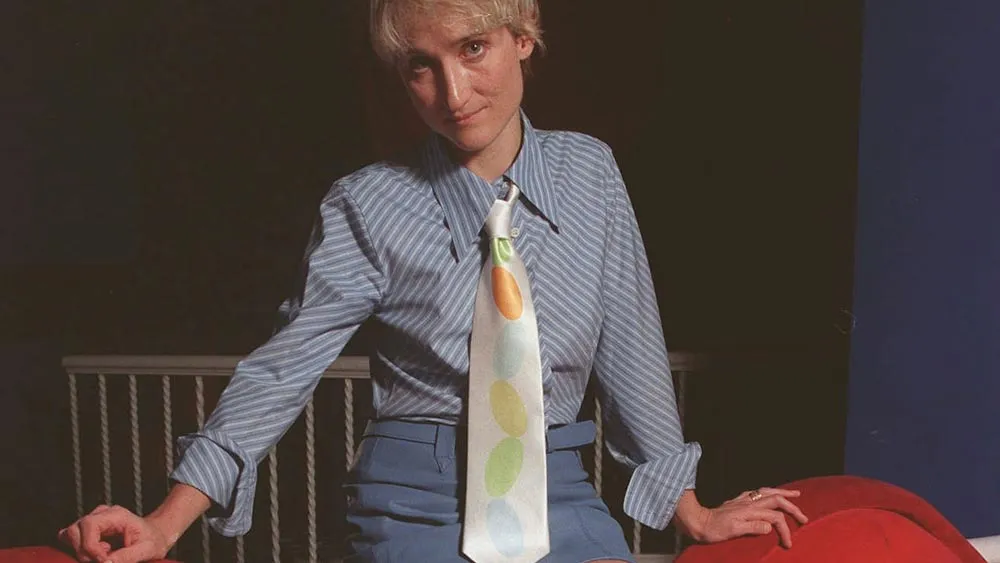

Those issues were soon overshadowed by the festival's screening of "The People's Joker," where director Vera Drew filters her life story as a trans woman breaking into comedy through Warner Brothers' various "Batman" movies. The only thing is that Drew never got clearance to use anything "Batman" related, and despite a disclaimer saying the film falls under fair use, Drew claims she was given a cease-and-desist order by Warner Brothers hours before the premiere. According to Polygon, the festival chose to defy the order and go ahead with the premiere, but hours later canceled all other screenings after Drew decided to pull the film.

When speaking to other festival attendees about the film's removal, I found a surprising amount of skepticism around the situation. From the beginning, both Drew and TIFF hyped up the film as either illegal or not meant to be seen, so the sudden withdrawal can come across as something like getting surprised by a bee sting after poking the bees' nest. Then there are the rallying cries over social media, campaigns to vote for the film to win the festival's People's Choice Award, and a slew of coverage that might otherwise have not happened had the film screened as planned. And then there's the bigger picture: Why would a festival like TIFF, which likes to see itself as the launchpad for Oscar hopefuls, piss off a major Hollywood studio they'll have to work with in the future? There may be outrage online and elsewhere, but on the ground there have been more questions of whether or not this is a marketing stunt.

I'd prefer to wait for more information (hopefully Drew releases the cease-and-desist order she received at some point), but a cynical response to "The People's Joker" and its legal woes is understandable in the context of attending a film festival. Hours before the premiere and only a few blocks down the street, director Laura Poitras criticized TIFF for inviting Hillary Clinton to promote a film she executive produced, which Poitras called "whitewashing" given Clinton's political past. These criticisms point to a bigger issue with TIFF and any other major film festival: marrying the progressivism of championing artists and diversity while engaging in business practices that run counter to those progressive values. As much as TIFF might love showcasing films from around the world that might otherwise not get seen, they also need to pay the bills, which means rolling out the red carpet for Hillary Clinton or inviting Taylor Swift in order to boost ticket sales, get donations, and woo potential corporate sponsors. It's all the messiness that comes from commerce crashing into art, which Vera Drew now finds herself in the center of.

No matter the circumstances, I hope to get to see "The People's Joker" and that all the publicity around the film will let any powers that be back off from trying to hide it away (unfortunately, Warner Brothers has taken to bad press like a fish to water, so we'll see how this pans out). In the meantime, TIFF continues on as usual with other titles like Martin McDonagh's "The Banshees of Inisherin," which just won prizes for Best Screenplay and Best Actor (for Colin Farrell) at Venice. This is McDonagh's first feature since the 2017 drama "Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri," which won the People's Choice Award at TIFF and also caused a stir over its portrayal of small town America, race relations, and various hot button issues.

This time, McDonagh returns to his family's homeland of Ireland to the fictional island of Inisherin during 1923, where the small population goes about their business while the Irish Civil War rages on in the mainland. Padraic (Farrell) goes to visit his close friend Colm (Brendan Gleeson) at the local pub, only to find Colm suddenly wants nothing to do with him. Colm tells Padraic he just doesn't like him anymore and to leave him alone, which throws Padraic into a crisis and snowballs into tragedy for both men.

McDonagh touches on ideas that were prevalent in "Three Billboards" here, like the folly of men creating cycles of violence that ripple outward and pull others into it. The specificity of the time period and isolated location lets him hone in on this one friendship, which makes the story developments and themes more potent. It's also extremely funny, with the reunion of McDonagh, Farrell, and Gleeson from "In Bruges" showing they're basically a dream team in terms of onscreen chemistry and comic timing (Barry Keoghan is another highlight, who plays the town outcast and goes around generally annoying the hell out of everyone). But like every McDonagh movie, its lasting power comes from how well he blends comedy with darker, more existential elements in the story, and with "The Banshees of Inisherin" it might be his best balancing act to date.

Since TIFF is based in Canada, it also doubles as a showcase of cinema in its home country, which led me to check out "Until Branches Bend," the feature debut from director Sophie Jarvis. Set in a small valley town called Montague (doubling for the gorgeous Okinagan Valley in British Columbia), it follows Robin (Grace Glowicki), who works at a peach farm and discovers a bug inside one of the peaches. She reports it to her boss (Lochlyn Munro) who downplays it, but Robin continues pursuing it until the local farms have to shut down over fears of an invasive species destroying the crops. The lack of work turns Robin into an enemy, with the town turning on her and collectively gaslighting her into thinking she made the whole thing up.

Jarvis' debut, while far from perfect, is one of the most promising first features I've seen all year. There's a bit of an obviousness to the symbols and themes, like the peaches and bugs along with a subplot where Robin tries to get an abortion, although none of these issues threaten to sink the film. Where Jarvis' strengths lie is in her subtlety, like the way her and cinematographer Jeremy Cox use 16mm film and the location in the Okinagan (a small town on flat land surrounded by looming mountains) to sustain a sense of unease within the sun drenched visuals. Glowicki is also a highlight as Robin, who carries a shy demeanor but a strong moral compass that, once it's attacked by almost the entire town, throws her into a gradual breakdown that Glowicki makes believable. I wouldn't put "Until Branches Bend" at the top of my list of films I've seen here, but after seeing dozens of films it's one of the few titles I still think about. It's part of why any film festival still has its purpose, since I'll come away from TIFF this year with a new filmmaker to keep an eye on in the future.